Of Flesh and Spirit

Rev. Michael J.V. Clark • July 3, 2025

Today’s parable, most commonly referred to as the Parable of the Prodigal Son, found in Luke 15:11-32, is often celebrated as a compelling illustration of God’s boundless mercy. The image of the father running to embrace his wayward son upon his return from a life of dissipation is a powerful testament to divine forgiveness. Yet, while

this aspect of the story rightly captivates our attention, there is another dimension to the parable worth exploring: the contrast between two categories of sin—sins of the flesh, and sins of the spirit—as embodied by the two brothers. By shifting our focus, particularly to the older son, we uncover a deeper truth about human nature and the subtle dangers that threaten our relationship with God.

But first a little theological anthropology. Human beings are a composite of body and soul, a union that gives rise to dual inclinations. On one hand, we are drawn to material comforts which satisfy the body—money, food, and physical pleasures—temptations we might call "beastly" because they align with the instincts we share with irrational beasts. On the other hand, we are also susceptible to spiritual temptations—for example, envy, prestige, or the desire for praise—which we might term "angelical" because they reflect the higher, immaterial aspect of our nature, akin to the spiritual beings created by God we commonly call, angels. All types of sin are serious, but the Parable of the Prodigal Son suggests that the angelical sins, exemplified by the older son, pose a greater peril precisely because of their clandestine nature.

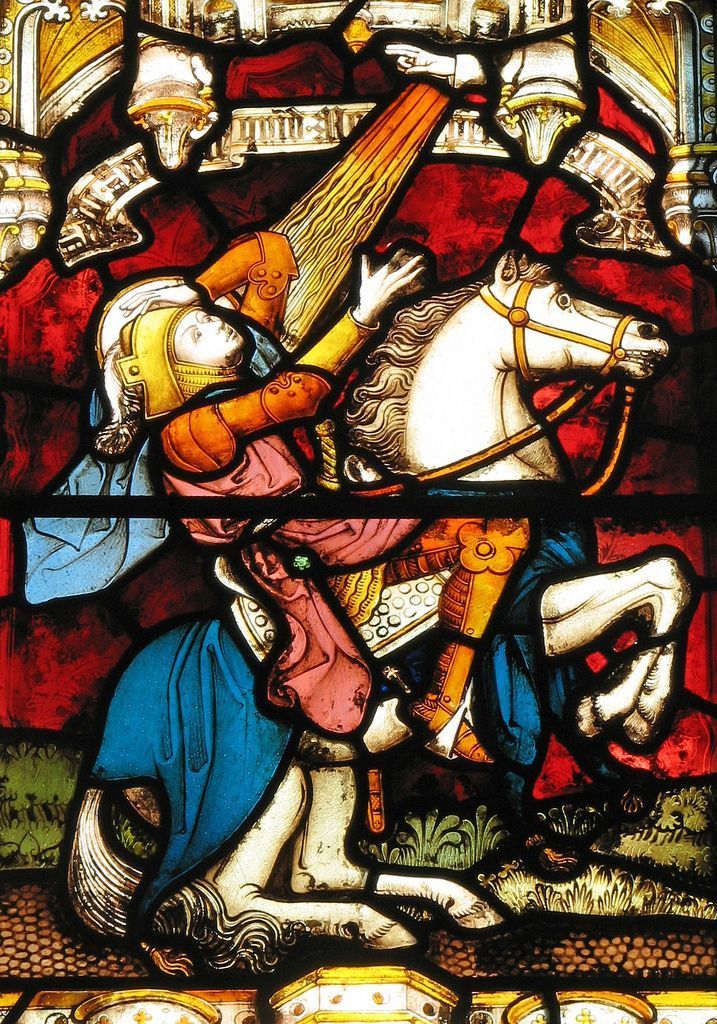

The younger son’s story is familiar: he demands his inheritance, squanders it in reckless indulgence, and eventually returns home humbled and repentant. His sins are of the flesh—self-evident and tangible. When his material resources run dry, he comes to his senses, recognizing the emptiness of his pursuits. His contrition is visible, his pathology clear, and thus, his return to the father is straightforward. He has chosen immediate gratification over lasting good, but his crisis forces him to confront this mistake, opening the door to reconciliation.

The older son, however, presents a more complex figure. Note he too receives his inheritance (so Scripture is careful to stress he has not been cheated) but he remains in his father’s house, outwardly obedient and dutiful. Yet, when the father celebrates the younger son’s return, the older son’s reaction reveals a cankerous, and deeply sinful heart. He accuses his father, saying, “Look, these many years I have served you, and I never disobeyed your command, yet you never gave me a young goat, that I might celebrate with my friends. But when this

son of yours came, who has devoured your property with prostitutes, you killed the fattened calf for him!” (Luke 15:29-30). His words betray a relationship with his father built not on love, but on a transactional sense of duty. He does not even call the prodigal one “my brother” but “this son of yours,” distancing himself both from his sibling and the father’s mercy. He is the great accuser, adding salacious detail to the narrative of which the father was previously unaware, as if that might revoke his mercy.

Pope Francis, in his Angelus address on March 22nd 2022, highlights this flaw: “The elder son bases his relationship with his Father solely on pure observance of commands, on a sense of duty. This could also

be our problem… losing sight that he is a Father, and living a distant religion, made of prohibitions and duties.” The consequence is a rigidity that blinds the older son to the familial bond he should share with his brother. His refusal to join the celebration—“he refused to go in” (v. 28)—symbolizes a self-imposed exile from the father’s love,

driven by pride and bitterness, but one that is interior. Outwardly, all is well; inwardly it is a mess.

Pope Benedict XVI, in Jesus of Nazareth, notes that for such people as the older son: “Their bitterness toward God’s goodness reveals an inward bitterness regarding their own obedience… In their heart of hearts, they would have gladly journeyed out into that great ‘freedom’ as well. There is an unspoken envy of what others have been able to get away with.” The older son’s obedience, though outwardly impeccable, is hollow. He has renounced immediate pleasures but he is angry about it. He harbors resentment, envying his brother’s

escapades while clinging to a self-righteous sense of grievance.

This contrast reveals a profound truth: sins of the spirit, like pride and envy, are actually harder to root out than sins of the flesh. The younger son’s dissipation is obvious and, in a sense, easier to treat because it is exposed by its consequences. He knows he has done wrong and seeks forgiveness. The older son, however, is more

pitiable. His sin is hidden, masked by his adherence to rules, and he feels no need for repentance. He believes he is in the right, yet his heart is further from the father’s than his brother’s ever was. As St. Paul writes, “If I have faith to move mountains, but have not love, I am nothing” (1 Corinthians 13:2). Without love, even the most rigorous

obedience is empty, and profits us nothing.

Our Lord underscores this in his teaching elsewhere: “The prostitutes and tax collectors are entering the kingdom of God ahead of you” (Matthew 21:31), he warns the scribes and Pharisees—those who, like the older son, reduce faith to a rule-based system. Obviously, the Lord does not condone the antics of prostitutes, or tax collectors, but he does note that their repentance is more sincere.

Christianity is not a checklist of obligations but a call to transformation: not “tell me what I must do,” but “tell me what I must be.” One in which the past does not govern the future. The father in the parable goes out

to both sons, offering love and reconciliation, yet only one accepts it fully. The younger son’s childish faith falters under temptation but matures through repentance. The older son’s faith, equally immature, cannot cope with the reconciliation of sinners, trapping him in a cycle of judgment and isolation.

The enduring legacy of Pope Francis’s pontificate may well be his challenge to this hypocrisy—calling out those who cling to regulations while secretly judging others in their hearts. We must repent of both types of sin, of course. The prodigal’s excess is not excused, but his visible struggle allows for a clearer path to healing. The older son’s spiritual cancer, rooted in pride, not unlike Satan and the fallen angels, is more treacherous because it festers unseen. It is a basic fact of pathology that a hidden infection is more difficult to treat.

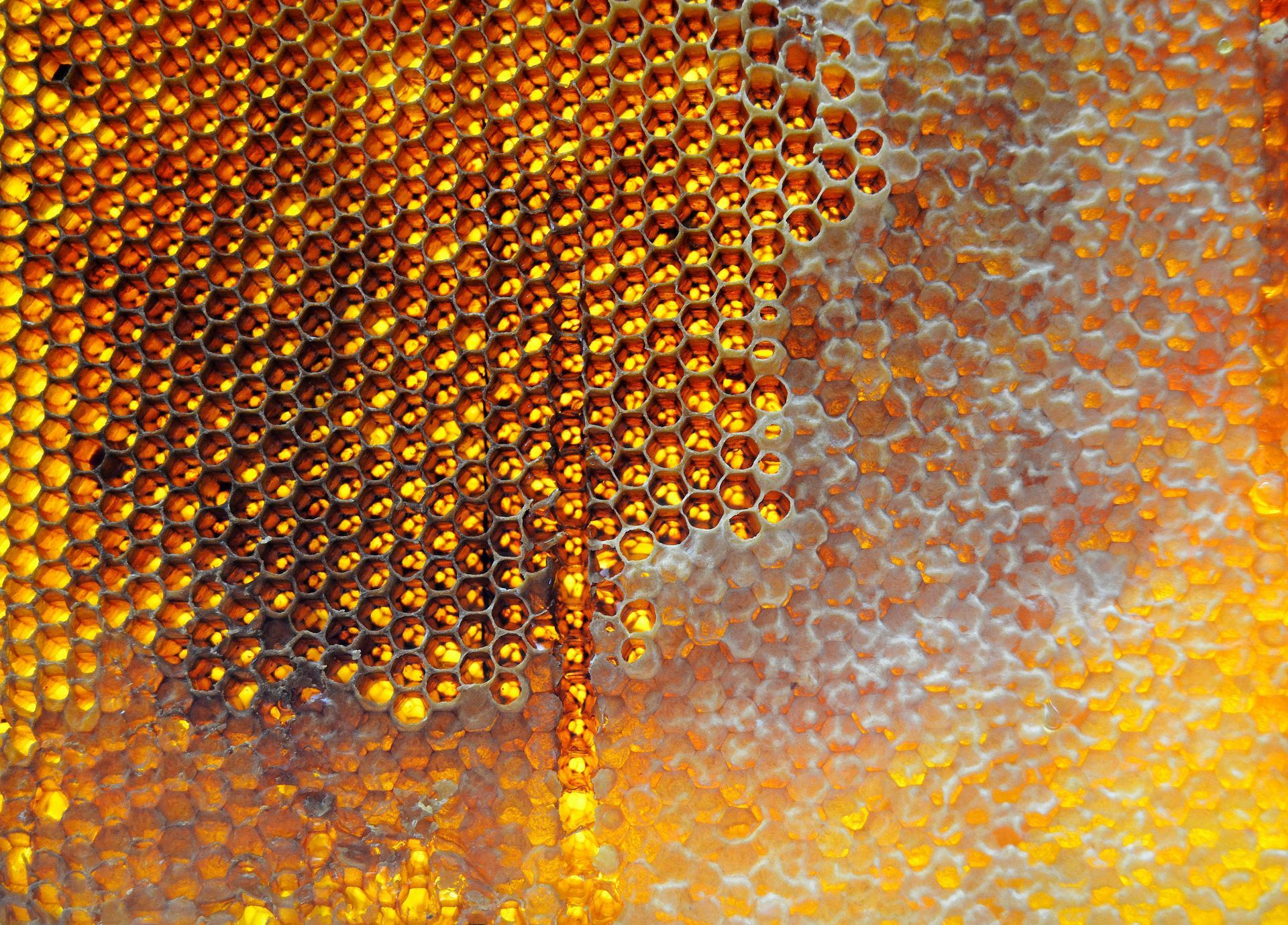

To live as true children of the Father, we must move beyond mere duty, embracing a faith grounded in love—for God, and for our brothers and sisters, prodigal or not. Only then can we recognize that the Father’s mercy is pure gift; entirely unmerited. He wishes to dress us with robe, ring, and sandals, but we cannot ever deserve it. To be like God is to be extravagantly generous, to give until the pips squeak, and to rejoice at the reconciliation of sinners.

Recent Posts